Summary

I’m a carnivore to the bone, pun intended. Meat is more often than not the centerpiece of my meals and the principal determinative of my wine selection. Despite this, as an animal lover I’ve always secretly admired those principled people who eschew the consumption of meat.

The recent adoption of non-meat foods at high-profile chains like Starbucks, KFC and others here in China is the topic of this paper’s gourmet sleuths. Faux meats have only recently become all the rage but mankind’s desire to use plant-based substitutes to emulate the flavor and texture of meats is far more ancient. Documents indicate that the Chinese used dough soaked in water and rinsed to make something that resembled pork during the Wei, Jin and the Southern and Northern dynasties (AD 220-589), then a few centuries later tofu first appeared in China.

In 1896, John Henry Kellogg, a member of the vegetarian belief Seventh Day Adventists, made a peanut-based product that resembled potted meat. As suggested by his surname, this is also the gent who popularized cereals as an alternative to heavy meat and egg breakfasts. But it wasn’t until the second decade of our new millennium that science enabled a meat substitute that genuinely resembled the meat experience. In 2013, Dutch researcher Mark Post created the first science laboratory burger from cultured cow cells. The drawback was that it cost US$325,000 to make a single patty and, because of the use of cow cells, wasn’t truly vegetarian.

The new age of faux meat began in earnest in 2013 when LA-based Beyond Meat started selling beyond chicken then beyond beef in Whole Foods Market stores. Silicon Valley startup Impossible Foods created the impossible burger that tasted and bled like a true beef burger. Last April, Burger King successfully launched their impossible whopper and other major restaurant chains like Carl’s Jr, A&W, Dunkin Donuts, KFC and McDonalds soon followed suit. This new age of veggie-based burgers and other faux meats has put the onus on wine aficionados to find a charming vino companion.

I must admit that I’ve never tried a faux burger but working on the assumption that they really do taste like beef burgers, then wine is a sure way to embellish the experience. Pairing a faux or real beef burger patty with wine is remarkably easy because there’s a plethora of red wines that match beautifully with anything that tastes like ground beef. It’s the topping that poses challenges because these condiments may include anything from ketchup, mustard, mayo, blue cheese, bacon, raw onion or even foie gras. Therefore, a must quality for burger-friendly red wines is versatility; so, whatever adorns your burger, the wine still tastes dandy. There’s a vastly underrated grape that does versatility in spades.

Gamay

It was in the 14th century during an outbreak of the Black Death plague that the Gamay grape first burst upon the winemaking scene. Related to the Pinot family and the obscure Gouais Blanc variety, the grape is named after a small hamlet in the Cote de Beaune.

Because of the overall hearty and vigorous nature of Gamay vines and the fact that it ripens about two weeks before Pinot Noir, by the end of the 14th century this red variety was supplanting its noble ancestor. In reaction, Philippe the Bold of the Duchy of Burgundy forbid the cultivation of Gamay in the prime growing areas of the Cote d’Or. This dogmatic Pinot-loving ruler promulgated that Gamay was “an evil and disloyal plant” and “injurious to the human creature.” Fortunately, the variety found a new home in the southern most reaches of Burgundy.

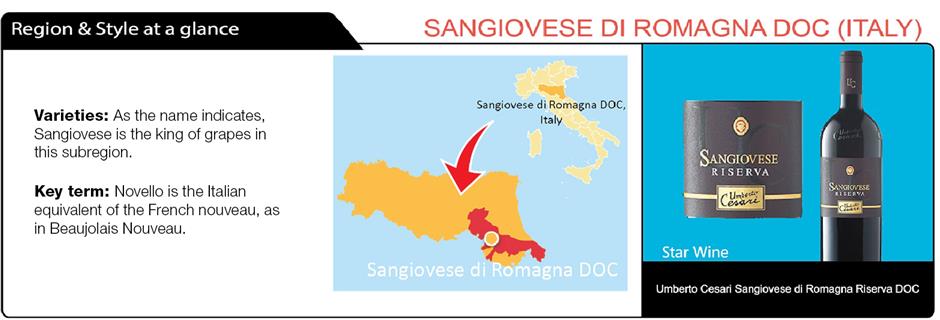

For centuries, Beaujolais Gamay wines enjoyed enviable reputations. This changed in the 1950s when profit-crazy, short-sighted winemakers started using artificial yeasts and chaptalization. The reputation of Beaujolais wines further waned in the 1980s and 1990s during the Beaujolais Nouveau craze.

In 2001, 1.1 million cases of mostly Beaujolais Nouveau had to be destroyed because the market for fruit-bomb wines had largely disappeared. Increasingly astute consumers moved on to better wines. In fact, throughout Beaujolais Nouveau fiasco, some winemakers continued to make excellent wines. Many of these were village or cru-level wines with depth, complexity and character. In these superior wines, the Gamay grape’s fruitiness still exists, but there are added layers of flavors and a longer more satisfying finish.

Cru Beaujolais wines stand at the apex of the Beaujolais quality pyramid. There are ten cru Beaujolais wines. All make fine wines but my favorites are Moulin-a-Vent, Chenas and Morgon because they tend to be the more full-bodied and complex. The best examples are also quite age-worthy.

In addition to choosing a village or cru-level wine, another key to Beaujolais-drinking success is choosing wines from the best producers. One shining star is Domaines Chermette that makes distinctive wines from old Gamay vines. Their Les Trois Roches Moulin-a-Vent AC wine comes from 40-year-old vines and beautifully exhibits the intensity and elegance of a top Cru Beaujolais wine. Other vino standouts from this producer include Les Grillades, Bouilly Pierreux from 60-year-old vines and the exceptional Coeur de Vendanges from century old vines. Additional recommended Beaujolais producers with wines in Shanghai include Joseph Drouhin, Louis Jadot and Thibault Liger.

Beaujolais is not the exclusive domain of fine Gamay wines, Domaine Serol in the Cote Roannaise AC is making some exceptional wines from the relative Gamay Saint Romain grape.

British Columbia and Oregon’s Willamette Valley are also making excellent Gamay wines, but alas these delicious topics must wait for a future column.

Where to buy in Shanghai

China Wine & Spirits, 702, no. 1, Lane 1136 Xinzha Rd, 6087-1811

Domaines Chermette Les Trois Roches Moulin-a-Vent AC

Domaines Chermette Les Grillades Beaujolais AC

Domaines Chermette Bouilly Pierreux AC

Domaines Chermette Coeur de Vendanges Beaujolais AC

www.everwines.com

Joseph Drouhin Beaujolais Villages AC

www.asc-wines.com

Louis Jadot Beaujolais Villages AC