Summary

Some claim it conquered the world. The humble potato flowering plant traces its origin some 350 million years ago in South America when it gradually evolved from the progenitor of the nightshade plant family that also parented chili peppers, bell peppers, tomatoes and tobacco. Over many millions of years, the plant distanced itself from its ancestors and evolved into wild potatoes. When humans first arrived over 15,000 years ago, these wild potatoes and their cousin plants proliferated the land.

No one really knows for sure but about 10,000 years ago humans first domesticated the potato plant in high altitude fields in what is modern day southern Peru and northeastern Bolivia. In the early 16th century, Spanish conquistadors discovered the potato and other New World plants and brought them back to Europe. The Europeans were slow to embrace the potato; but when they did, they did so in a big way. There are compelling reasons why.

Europeans soon discovered that as a crop, potatoes distinguish themselves by their ease of cultivation, transport and storage. Most important, per hectare yield and pound for pound the potato offers unmatched nutritional value; significantly more than the staple grains of rice, corn and wheat. In his 1999 essay, “How the Potato Changed World History,” historian William McNeill states that, by efficiently feeding rapidly growing populations, the potato allowed a handful of European nations to assert domination over most of the world between 1750 and the early 20th century. Wow, perhaps the potato did indeed conquer the world.

China’s adoption of the potato has been less all-encompassing than that of Europe and the Americas. Believed to have been introduced to China by Dutch and Portuguese traders during the mid 1600s, the potato has played a secondary role to rice and wheat in Chinese cooking. Nonetheless, China is the world’s largest producer of potatoes and northern and western regions boast a variety of delicious potato creations.

By themselves, potatoes are wine neutral, meaning there’s a wide range of accommodating wine partners. Therefore, the art pairing potatoes with wines is all about the ancillary ingredients and method of cooking. One emerging style of Spanish white wine pairs beautifully with a wide range of Chinese and Western potato preparations.

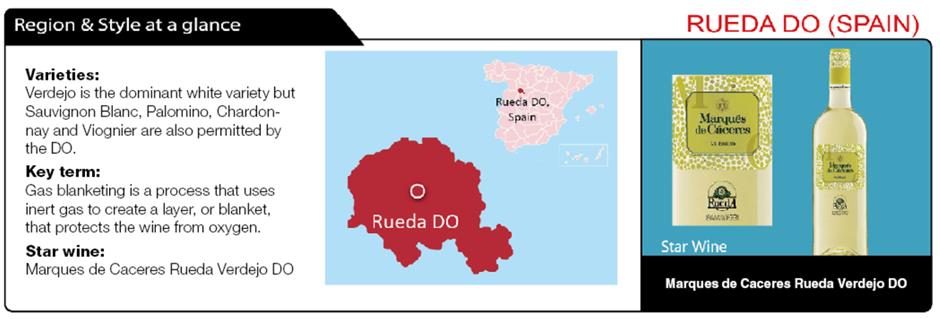

Rueda Verdejo DO

Nearly a decade ago I traversed the rough and wild landscape of Rueda, part of the large Castilla y Leon region of Spain. Back then the white wines of Rueda were just beginning to be recognized by a larger international following. But I was impressed by the intrinsic quality and distinctive character. Some of the wines were still a bit rough and rustic. Like the landscape, the exuberance, intensity and personality of the wines were clearly distinguishable. I became a fan, not only of the wines but of the place and its special beauty and history.

Rueda is white wine country, more specifically its Verdejo country. This aromatic variety is believed to have originated in North Africa, likely what’s present day Morocco, and migrated to the Iberian Peninsula sometime around the 11th century. Some say the Moors brought the vine; however, as Sunni Muslims it’s a stretch to think they were motivated to transport and cultivate a specific variety. The peninsula already offered a range of vines suitable for the medicinal purposes of the Moors. More likely, the Christian Mozarabs brought the grapes from Africa to Spain, and the transplanted variety made its way to Rueda where it found its spiritual home. The journey wasn’t easy.

After a devastating phylloxera in the latter part of the 19th century, vineyards in Rueda were primarily planted with the pest resistant Palomino variety. These grapes were mostly used to make fortified wines. Fortunately, small lots of Verdejo survived and a few vineyards were replanted with the grape but these grapes made wines almost exclusively consumed by the locals and remained mostly anonymous.

Verdejo’s century-long exile in purgatory witnessed embers of hope in the early 1970s when the famous Rioja winery, Marques de Riscal, recognized hidden potential of the obscure variety in the remote rugged hills. Other wineries followed suit and by the turn of the century Verdejo enjoyed a growing cadre of wine aficionados in Spain and around the world. Rueda Verdejo DO wines must comprise a minimum of 85 percent Verdejo with minority contribution of Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay and Viognier allowed.

Good examples of Rueda Verdejo wines typically feature a vivid yellow-green color, citrus and grassy aromas and flavors with herb and spice notes. Older wines tend to offer intriguing tropical fruit and nutty sensations. A common denominator to all well-made wines is freshness and weight on the palate. Most Verdejo whites are fermented and aged in stainless steel to emphasize aromatics and purity, though a few producers are doing both processes in oak or concrete vats to add greater depth and texture. Barrel-fermented wines can be kept for 5-7 years, while unoaked wines are best within 3-4 years of release. Marques de Caceres, De Alberto and Marques de Riscal have lovely barrel-fermented and unoaked Rueda Verdejo wines available in Shanghai. Other fine producers include Valdelosfrailes, Pata Negra, Visigodo and Juan Galindo.

The intensity and balance between fruitiness and acidity make Rueda Verdejo wines lovely companions to a myriad of Chinese potato dishes, including sour and spicy potato juliennes, Northeast-style potato, eggplant and bell pepper stir-fry and Sichuan potato pancake. Verdejo wines pair equally well with Western potato classics like English fish and chips, French potato gratin, Canadian poutine and American-style chili fries.

Where to buy in Shanghai

www.yesmywine.com

Valdelosfrailes Rueda Verdejo DO

www.vinehoo.com

Pata Negra Rueda Verdejo DO

Visigodo Rueda Verdejo DO

Juan Galindo Rueda Verdejo DO

ruedado.1688.com

Marques de Caceres Rueda Verdejo DO

Marques de Caceres Emna Rueda Verdejo DO

De Alberto Rueda Verdejo DO